Eligibility & Education Can Make the Difference

In 2018, I was lucky enough to have an internship with Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) at Temple University Hospital (TUH). During my internship, I was able to experience firsthand the process for finding participants for clinical trials conducted at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, follow the progress of the participants, and conduct educational sessions about clinical trials to potential participants. While at Fox Chase, I recognized the participant crisis in clinical trials—specifically, the lack of diversity in patient participation. Clinical trials are critical for the development and improvement of medicines; yet how can these medicines be properly tested if not on a diverse population?

Community Demographics: Key to Diverse Enrollment

In getting to know the urban population that surrounded Temple University, this topic of equitable healthcare access became very important to me. Let’s start with an analysis of those neighborhoods. Of the 633,031 in the service area of TUH, 47% of the population is African American, 24% are Latino, 21% are white, and 6% are Asian (Public Health Management Corporation, 2016). I think it is interesting to note that at the time of this research, no other FCCC had such a high percentage of African Americans in their community. Research has found that when trying to recruit individuals into clinical trials, African Americans and those considered middle income respondents were dramatically less likely to participate in clinical trials (Baquet, Commiskeym Mullins, and Mishra, 2012). When researching eligible criteria for clinical trials, most clinical trials have included a limited slice of the overall population and have overly represented those who are married white males that are not from lower socioeconomic levels (Swanson & Ward, 1995). What we should we gather from the above statistics and information is that populations are incredibly diverse, especially at TUH, and these populations have a variety of economic statuses and education levels, all factors that should be considered when finding participation for clinical trials.

A key factor when looking at this population and location is education and socioeconomic status. Sixty two percent of TUH service residents are high school graduates and just 13% have a college degree or more (Public Health Management Corporation, 2016). 26% of this population did not graduate high school (Public Health Management Corporation, 2016). When researching barriers to clinical trial participation, education is a common concern.

Analyzing Potential Participants & Eligibility

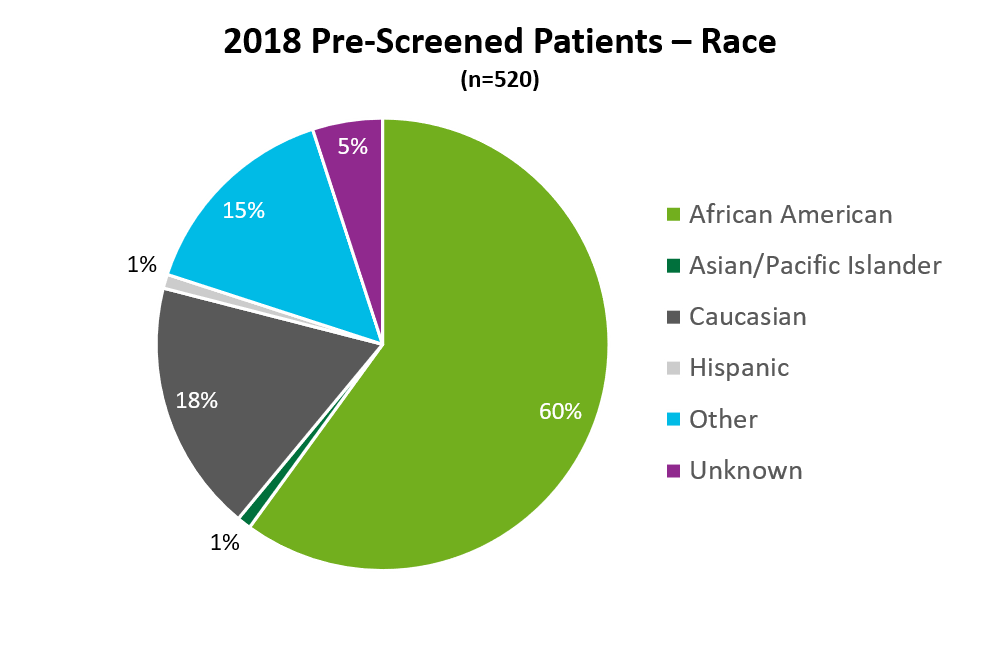

During my internship I analyzed “screening reports” that would list all eligible patients for clinical trials, inclusive of ethnicity, race, and preferred language. The total number of patients present on the tracker report was 520 as represented in the pie chart below (African American patients = 312, Caucasian = 92, Hispanic = 44, Asian/Pacific Islander = 6, those patients who identified as “other” = 78, and those patients who were “unknown” = 25).

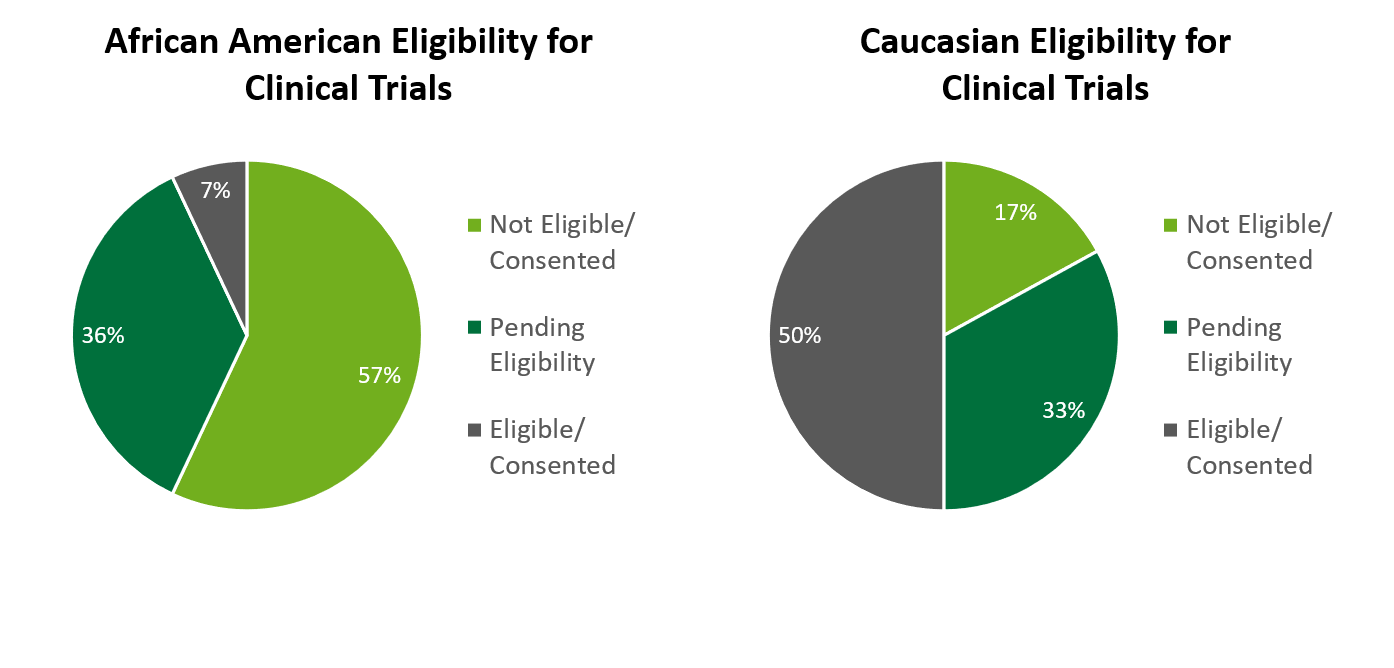

Out of the 312 that were identified African American, it was found 57% were ineligible to participate or did not consent, 36% were still pending eligibility, and just 7% were found eligible and consented. When compared to Caucasian patients at TUH, I found that 50% of Caucasian patients were found eligible or could consent, compared to 7% of African American patients, and 17% of Caucasian patients were found ineligible or did not consent, compared to 57% of African American patients, this is a major difference in the percent of consented/eligible African American patients compared to Caucasian. The common reasons cited for ineligibility among African American patients was refusal, the patient became deceased, ineligible (due to not meeting IRB criteria), and other (getting treatment elsewhere, on another trial, or taking another medication). The races of Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Other and Unknown were grouped together due to their low number of pre-screened patients. Fifty percent of these ethnicities were found eligible or could consent, 33% were pending eligibility, and 17% were found not eligible or did not consent. Language barriers were a common concern as well as they related to approved consent or needing a translator.

Making Education About Clinical Trials Fun

My next task was performing an informational bingo session about clinical trials. I surveyed participants before the informational session as well as afterwards to see if providing education on clinical trials would change the patients’ negative views. There were 23 participants in the bingo sessions total, and 61% were African American.

Two questions were found to have a significant difference in responses. For Question 1, “I understand why clinical trials are important”, a significance value of p = .011 was found, meaning patients agreed more with this statement after the informational session. For Question 2, “I worry that I will be put on a clinical trial and not know it”, a strongly significant value of p =.006 was found, patients disagreed more with this statement after the information session.

Reflections on Patient Eligibility and Education

From this research, I was able to determine two areas of concerns for clinical trials: patient eligibility and patient education. First, 60% of the screened patients were African American, which was more than triple the number of Caucasian patients. When comparing eligibility between African American and Caucasian patients, only 7% of African American patients were found eligible or consented, compared to 50% of those who identified as Caucasian. Examining the reasons behind ineligibility criteria for all races of pre-screened patients can provide insight on those who might need more education on what clinical trials are to want to participate in them, or perhaps show that all languages should somehow be incorporated into clinical trial and IRB protocols. Second, the clinical trial education session showed that providing education to participants and providing education to participants helped to change participants’ perspectives toward clinical trials in a positive way.

Education and Awareness are Critical for the Future of Clinical Trial Diversity

With COVID-19 trials so prevalent in today’s world and developing this vaccine to help stop the pandemic, education and awareness of clinical trials is critical. Suggestions on how to improve the view of clinical trials in diverse communities were mentioned previously in this report. One of those ways was by creating a community awareness model that helps educate and inform individuals (Harris et al., 1996). Educational sessions can help potential participants understand more about clinical trials and should be used in health care settings to help promote participation. Removing barriers such as language and costs and providing education about clinical trials are critical points of improvement for diverse clinical trial participation. I plan to continue to focus on diversity in trials in my work at Greenphire as well as research and examine the population of the COVID trials/vaccine.

References

Baquet, C. R., Commiskey, P., Mullins, C. D., & Mishra, S. I. (2006). Recruitment and participation in clinical trials: socio-demographic, rural/urban, and health care access predictors. Cancer Detection and Prevention, 30(1), 24–33. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdp.2005.12.001

Harris, Y., Gorelick, P.B., Samuels, P., & Bempong, I. (1996). Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. Journal of National Medical Association, 88(10). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2608128/pdf/jnma00387-0030.pdf

Miranda, J., Nakamura, R., & Bernal, G. (2003). Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: A practicial approach to a long-standing problem. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 27(4), 467-486. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guillermo_Bernal/publication/8915561_Including_Ethnic_Minorities_in_Mental_Health_Intervention_Research_A_Practical_Approach_to_a_Long-Standing_Problem/links/0fcfd512404593192a000000.pdf

Public Health Management Corporation. 2016. Temple University Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment. Retrieved from https://tuh.templehealth.org/upload/docs/TUHSPUBLIC/TUH-CHNA-2016.pdf